Detail from Vermeer - The Milkmaid

There was a boy, who had no name of his own, but who came to be called Martin.

He had no name because he was a foundling, left beneath the cross on the village green one warm summer night, and found next morning when the Parson was taking his morning walk.

Old Sef the Baker took the foundling in, and called him Martin, because he and his wife wanted a son and had only girls. Martin was mighty spoiled by all those women – they let him do pretty much what he pleased, but there was never any harm in the lad. He liked to be with animals – from the time he could walk, he never slept in the house, he preferred the barn with the dogs and the hens and the bakery horse.

Old Sef took him into the bakery when he was about ten summers old, and taught him all he needed to know to grind the corn and make the bread that was sold from the back of the horse dray. Then, having seen to it that the business was in good hands, Old Sef up and died and left Martin to take over.

His sisters had all married, and Martin lived with his adopted mother until she died. Then Parson called on him, to advise him that it was time he took a wife. Parson frowned on bachelors – they caused no end of trouble, he said, like a fox loose in the hen house.

Parson had already made a list of suitable young women, but to his dismay Martin would have none of them. He said he would find his own wife, and that she would be made of leaves and sunshine and droplets of dew.

``I’ve never heard such heathen ravings,” Parson huffed as he walked across to the Inn to save some souls. ``What’s he planning to marry, a scarecrow from farmer Bryn’s field?”

Martin took to spending long hours away from the village after the day’s work was done and the bread sold. He was seen heading off in the direction of the woods, then was seen to return around daybreak. Whispers flew about that he had found himself a fancy woman in the next village. True to his wild ways, they said, Martin would never marry and settle down like a normal man.

But then one day invitations arrived to Martin’s wedding on the green. Even Parson, although he was not required to officiate, was invited as a guest. To his disgust it was to be a handfast wedding, with the two leaping over a broom at the end to seal their union.

``An abomination,” he declared, but he turned up anyway and drank as much good cider as any man there.

Everyone was curious to see the bride. All the children in the village, who loved Martin, went out early to gather flowers in the woods and filled baskets to the brim with primroses, daisies, buttercups and wild wood roses.

At midday, a faint piping was heard in the distance. It was coming from the direction of the woods.

As the villagers watched, open mouthed, the strangest party ever seen came out of the woods. They might have been gypsies, so brightly and gaily were they dressed, but there were no wagons lumbering in their wake. All were on foot, and those feet bare as they tripped over the grass to the music.

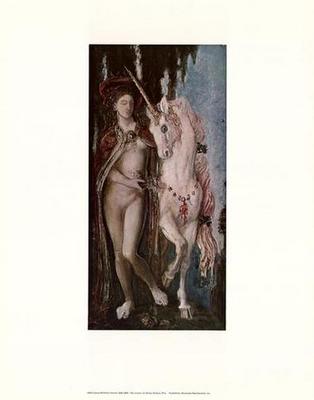

One, a young woman as tall and fair as a young birch tree, walked ahead of them. Her hair fell almost to her knees, so fine spun and golden it was like the sun streaming about her. In her hair, she wore a circlet of flowers. Her eyes were green, and she wore a dress like rustling leaves.

Then Martin came out of the bakery – his feet were also bare and he joined hands with the fey girl, and the strange folk from the woods gathered around them, singing to the notes of the pipe.

An old woman joined their clasped hands with a rope so fine it looked like cobwebs with the dew still sparkling on them. The old woman, dressed in rainbow colored robes, then produced a besom, and laid it on the grass. Martin and the fey girl leaped over it together and the wood folk burst out laughing and clapping and everyone joined in.

``Hail Martin and Lilyflower,” cried the man with the pipe, and started playing again. This time the music was for dancing and everyone clasped hands, even Parson, and ringed the young couple as they stood together on the green.

They danced long into the night, but by morning the strange folk were gone, and Martin and Lilyflower began their married lives at the bakery.

In a year, Lilyflower had borne a child, a girl as pretty as herself, and then another year later there was a son, nut brown and dark haired like his father.

All worked in the bakery, and the bread they produced was the finest in the land. From dark rich seedy loaves to soft cakes, eating it was like eating light itself. When illness threatened the village, Martin and Lilyflower would bake up loaves that looked like they were made of marigolds and sunshine, and which tasted like nectar. Within an hour of eating them, these loaves sent colds and sniffles packing.

As word traveled of the wonderful bread, people came from far away to buy them, but many were disappointed. Martin and Lilyflower baked as much as they could, but many still went away empty handed. But that didn’t stop them coming.

Sometimes they would camp on the edges of the village, and queue outside the bakery hoping to be first to buy the bread. But Martin and Lilyflower always sold bread to the villagers first.

This caused some trouble – fights broke out, and when Parson pleaded with the strangers to move on and leave the village in peace, he was pelted with clods of earth. To get rid of them, Martin and Lilyflower sold them the bread they had baked, and then started again, making bread for the villagers.

But that night the village slept ill, dreading the return of the people from far away demanding the morning’s bread. But when the villagers awoke in the morning, the strangers were gone. So were Martin, Lilyflower and the children.

All that was left around the empty bakery was some scattered leaves, with the morning sun drying the dew on them.

Parson stood looking at the bakery for a while, then went inside. The villagers crowded round the door and watched him lighting the fires under the ovens, mixing the grain and the yeast and kneading big slabs of dough. Soon a few of the villagers had joined him, and he led them in rousing hymns as they baked bread for the day.

As for Martin – it is said he now resides in an old mill on the way to a certain gypsy camp, where he set up a bakery. In the early morning, when the scent of newly baked bread wafts down from the mill, you can go and listen to his tales.